Part one of the two-part series examines the rhetoric framing immigration reform

This is part one of a two-part essay on immigration. Part two will be published next week.

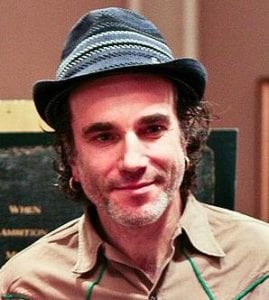

Would you recognize an undocumented immigrant if you met one? What if he were a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who has written for the Washington Post, The Huffington Post and The New Yorker?

In an essay in The New York Times Magazine to come out on Sunday, June 26, Jose Antonio Vargas revealed publicly for the first time that he not only came to the U.S. without proper documentation, but he has not since been naturalized and remains an undocumented immigrant to this day.

The essay is moving, emotional and hard to ignore. One day after its early publication online, it has already received over 700 comments, most of them messages of support for Vargas.

Last December, the DREAM Act was once again shot down in Congress, though it came frustratingly close to success for the student activists who had played a critical role in thrusting it into the spotlight —

the DREAM act passed the House of Representatives on December 8, but on December 19 the Senate couldn’t break through with a vote, effectively killing it.

Vargas, who was sent to the U.S. from the Philippines at age 12 and went on to graduate from both high school and San Francisco State University, would have been granted legal permanent resident status under the DREAM Act, at least as far as I understand it.

The “DREAM Act” is actually has been around since 2001 in various versions, but the basics are largely the same: undocumented immigrants who arrived as minors before age 16 (and have lived in the U.S. for at least five consecutive years since) and have graduated, earned a G.E.D. or been accepted into an institution of higher learning would be granted a conditional residency of six years.

In that six years, the student must either receive a degree, complete 2+ years in good standing of a degree program and be working toward a degree, or serve at least two years in the military. And of course, this is all predicated on being of “good moral character” (a legal concept) — if the student is convicted of certain crimes, for example, he would be unable for the six-year temporary residency. People already in their six-year residency term would lose their residency status.

So Vargas, whose essay lays out his story with such emotion that I’m not even going to attempt to summarize it, would have been given permanent residency under the DREAM Act.

Too bad.

Instead, Vargas has had to hide a critical part of his life from employers and friends, which he says has kept him from romantic relationships and growing close to friends.

When Vargas, as part of a team at The Washington Post, received a Pulitzer Prize in 2008 for coverage of the Virginia Tech shootings, his grandmother called him on the day of the announcement to ask him what would happen if people found out about his status as an undocumented immigrant.

“I couldn’t say anything. After we got off the phone, I rushed to the bathroom on the fourth floor of the newsroom, sat down on the toilet and cried,” Vargas writes.

With issues like immigration reform, it’s often easier emotionally to think of people in groups and stereotypes rather than as individuals, which leads to the fights where one side uses sweeping generalizations to make arguments while the other uses individual stories to try to generate sympathy.

To have a proper conversation about immigration reform, we need to be able to reconcile both sides in this at least: recognize that legislation is necessarily a broad move affecting large groups but that those groups are made up of individual stories. That’s where we need to start. Neither side is wrong, but that doesn’t make them right, either.

This is a problem with all major issues, as far as I can tell. All sides engage in rhetoric designed to be impenetrable and no one gets anywhere. A heartbreaking story of a child getting deported and stereotypes of Mexican orange pickers don’t counter each other, they just serve to divide everyone even more.

Next week, I’ll dive deeper into immigration reform, but the ground rules have to be set before we can even have that conversation.

To be clear, I have nothing against Vargas or his essay. I think it’s a compelling story that raises the issue of undocumented immigration in a way that’s hard to ignore. At the same time, I don’t think it stands alone as any reason to support immigration reform in a specific way — we shouldn’t pass the DREAM Act because of Vargas’s case, in my opinion, we should pass it because Vargas represents a subset of kids who face the same issues every day.

I’m also going to use the term “undocumented immigrant” instead of “illegal alien” or “illegal immigrant,” a personal editorial choice. I don’t think that there’s anything wrong with the other terms, necessarily, since I don’t care about the semantic fights over language. I understand why some people say that people are “never illegal,” but the real fight’s not over “illegal” versus “undocumented,” and it certainly sounds better than saying “criminals,” which technically you are if you break U.S. law. But because Vargas sparked my blog posts, I’ve chosen to use the term “undocumented immigrant” out of respect for him. His choice was clear, and when I’m talking about him I’ll respect that.

So next week, let’s have an open-minded conversation about “undocumented immigration” and immigration reform, and let’s be both clear and honest as we do so. Check your fighting spirit at the door and bring your open minds, because this is about reflection, not rhetoric.

To read Jose Antonio Vargas’s essay “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” click here.